Total Internal Reflection

Technology and Art

Code

Contact

Functional Analysis Exercises 3 : Sets, Continuous Mappings, and Separability

This post lists solutions to many of the exercises in the Open Set, Closed Set, Neighbourhood section 1.3 of Erwin Kreyszig’s Introductory Functional Analysis with Applications. This is a work in progress, and proofs may be refined over time.

1.3.1. Justify the terms “open ball” and “closed ball” by proving that (a) any open ball is an open set, (b) any closed ball is a closed set.

Proof:

The definition of an open ball is:

\[B(x_0,r)=\{x: d(x,x_0)<r, x \in X\}\]This implies that every point in the open ball is separated from \(x_0\) by some distance \(r-\epsilon\), \(\epsilon > 0\). Assume such a point \(p\), then we have \(d(p,x_0)=r-\epsilon\). Assume a point \(y\) in an open ball of radius \(\epsilon\) centered on \(p\). We then have: \(d(y,p)<\epsilon\). Then we can see that:

\[d(y,x_0) \leq d(y,p) + d(p,x_0)<\epsilon + (r-\epsilon)=r \\ \Rightarrow d(y,x_0)<r\]Hence, we can have an open ball of some size \(\epsilon\) around every point \(x\) in the open ball.

Hence, an open ball is an open set.

\[\blacksquare\]The definition of a closed ball is:

\[\overline{B}(x_0,r)=\{x: d(x,x_0)\leq r, x \in X\}\]Then the complement of \(\overline{B}(x_0,r)\) becomes:

\[U=\overline{B}(x_0,r)'=\{x: d(x,x_0)>r, x \in X\}\]This implies that every point in the complement of the closed ball (call it \(U\)) is separated from \(x_0\) by some distance \(r+\epsilon\), \(\epsilon \geq 0\). Assume such a point \(p\), then we have \(d(p,x_0)=r+\epsilon\). Assume a point \(y\) in an open ball of radius \(\epsilon\) centered on \(p\). We then have: \(d(y,p)<\epsilon\). Then we can see that:

\[\require{cancel} d(p,x_0) \leq d(p,y) + d(y,x_0) \\ \Rightarrow r+\cancel\epsilon < \cancel\epsilon + d(y,x_0)\\ \Rightarrow d(y,x_0) > r\]Thus, an open ball \(\{y: d(y,x)<\epsilon, y \in U\}\) can exist around any \(x \in U\). Thus, \(U\) is an open set.

The complement of the open set \(U\) is the open set \(\overline{B}(x_0,r)\). Hence, a closed ball is a closed set.

\[\blacksquare\]1.3.2. What is an open ball \(B(x_0;1)\) on \(\mathbb{R}\)? In \(\mathbb{C}\)? (Cf. 1.1-5.) In \(\mathbb{C}[a,b]\)? (Cf. 1.1-7.) Explain Fig. 8.

Answer:

The open ball \(B(x_0;1)\) on \(\mathbb{R}\) is the open interval \((x_0-1,x_0+1)\).

The open ball \(B(x_0;1)\) on \(\mathbb{C}\) is the unit disk centered at \(x_0\), excluding its circumference.

The open ball \(B(x_0;1)\) in \(\mathbb{C}[a,b]\) is the set of functions \(x(t)\) which satisfy the condition \(\sup\vert x_0(t)-x(t)\vert < 1\).

1.3.3. Consider \(C[0,2\pi]\) and determine the smallest \(r\) such that \(y \in \overline{B}(x;r)\), where \(x(t)=\text{sin }t\) and \(y(t)=\text{cos }t\).

Answer:

The center of the ball is \(x=\text{cos } t\). The point \(y=\text{cos } t\) needs to be in this ball. This gives us the condition that the \(y\) can at most be on the boundary of the ball. The radius of this minimal ball then becomes:

\[r_{xy}(t)=x-y=\text{sin } t-\text{cos } t\]We need to minimise the above expression, thus differentiating \(r_{xy}\) with respect to \(t\) and setting it to zero, we get:

\[\frac{dr_{xy}(t)}{t}=\text{cos } t+\text{sin } t=0 \\ \Rightarrow \text{tan } t = -1 \\ \Rightarrow t = -\frac{\pi}{4}\]Plugging this value back into that of \(r_{xy}\), we get:

\[\min r_{xy}=-\sqrt{2} \\ |\min r_{xy}|=\sqrt{2}\]1.3.4. Show that any nonempty set \(A\subset (X,d)\) is open if and only if it is a union of open balls.

Proof:

An open ball is defined as:

\[B(x_0,r)=\{x: d(x,x_0)<r, x \in X\}\]Assume that \(A\) is open. Then every point \(x\) in it has an open ball around it, such that \(B_\epsilon(x,r) \subset A\) for some \(\epsilon>0\). Hence, the union of open balls \(\bigcup\limits_i B_i(x_i, r) \subset A\).

Also, all the open balls in \(\bigcup\limits_i B_i(x_i, r)\) contain all the points in \(A\). We can say \(x \in \bigcup\limits_i B_i(x_i, r), x \in A\). Thus the union “covers” \(A\), or contains \(A\). Thus, \(A \subset \bigcup\limits_i B_i(x_i, r)\)

Putting the above set relations together, we get:

\[A=\bigcup\limits_i B_i(x_i, r)\] \[\blacksquare\]Assume that \(A\) is a union of open balls \(\bigcup\limits_i B_i(x_i, r)\). Then any point \(p\) in a given ball \(B_i(x_i,r)\) with a radius of, say, \(\epsilon\), can have an open ball around it of radius \(\epsilon'=\min\left(\displaystyle\frac{d(p,xi)}{2}, \frac{\epsilon-d(p,x_i)}{2}\right)\), while being a member of \(A\). Since \(p\) is an arbitrary point in \(A\), \(A\) is an open set.

\[\blacksquare\]1.3.5. It is important to realise that certain sets may be open and closed at the same time. (a) Show that this is always the case for \(X\) and \(\emptyset\). (b) Show that in a discrete metric space \(X\) (cf. 1.1-8), every subset is open and closed.

Proof:

The empty set \(\emptyset\) has no elements, and thus contains (vacuously) all its limit points, and is thus closed. All the elements in \(\emptyset\) contain (vacuously) open balls around them, and thus the empty set is also open.

Since \(X\) is the complement of \(\emptyset\), it is also open and closed by the same token.

1.3.6. If \(x_0\) is an accumulation point of a set \(A \subset (X,d)\), show that any neighbourhood of \(x_0\) contains infinitely many points of \(A\).

Proof:

An accumulation point for a set \(U\) contains at least one \(x \in U\) in every neighbourhood. Since we can always find a smaller neighbourhood than the one chosen, we can find an infinite number of neighbourhood smaller than an arbitrary neighbourhood, hence that neighbourhood will contain an infinite number of points.

1.3.7. Describe the closure of each of the following subsets:

(a) The integers on \(\mathbb{R}\)

(b) the rational numbers on \(\mathbb{R}\)

(c) the complex numbers with rational real and imaginary parts in \(\mathbb{C}\), (d) the disk \({z: \vert z \vert < 1}\subset C\).

Answer:

(a) Any sequence of integers can only have an integer as its limit point. Thus, all the limit points are the integers themselves. Thus, the closure of the integers on \(\mathbb{R}\) is the set of integers themselves \(\mathbb{Z}\).

(b) All real numbers are defined as the limit point of sequences of rational numbers. Thus the closure must include the rational numbers \(\mathbb{Q}\), as well as the real numbers. Thus the closure is \(\mathbb{R}\).

(c) Looking at (b) above, we can conclude that the closure is \(\mathbb{C}\).

(d) The closure of \({z: \vert z \vert < 1}\subset C\) is the unit disk centered at the origin (including the circumference).

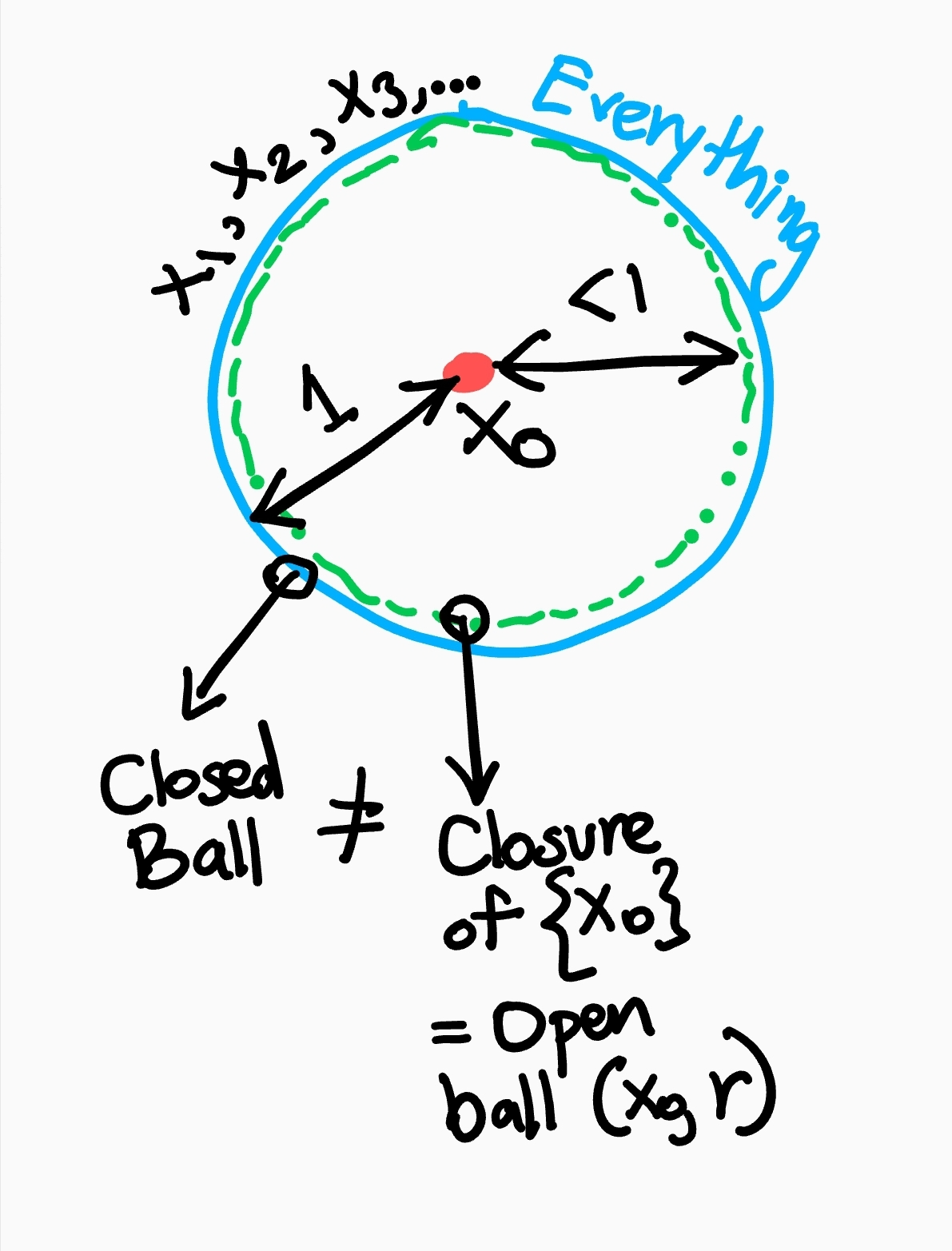

1.3.8. Show that the closure \(\overline{B(x_0; r)}\) of an open ball \(B(x_0; r)\) in a metric space can differ from the closed ball \(\overline{B}(x_0; r)\).

Proof:

We use a counter-example to prove this.

We describe the pathological case where the closure of an open ball is not the closed ball.

In a Discrete Metric Space, an open ball around an element \(x_0\) is \(d(x,x_0)<1\) is \(X=\{x_0\}\). Since there is no other \(x\) within every any neightbourhood of \(x_0\), which is not \(x_0\) itself, \(X=\{x0\}\) has no limit points. Then \(X=\{x_0\}\) vacuously contains all its limit points (of which there are actually none, so the empty set is the set of limit points). Thus, \(\overline{X}=\{x_0\}\) is its own closure.

The closed ball around \(x_0\) is \(d(x,x_0)\leq 1\), which is everything, but it is not the same as \(\overline{X}=\{x_0\}\).

The situation is shown below:

1.3.9. Show that \(A \subset \overline{A}\), \(\overline{\overline A} = \overline{A}\), \(\overline{A \cup B} = \overline{A} \cup \overline{B}\), \(\overline{A \cap B} \subset \overline{A} \cap \overline{B}\).

(This proof is due to Strichartz)

Proof:

The closure of the set \(A\) contains the set \(A\) as well as its limit points. By that definition, we can say that \(A \subset \overline{A}\).

Suppose additional limit points exist for \(\overline{A}\) which are then in \(\overline{\overline A}\). Take such a limit point \(x\). Since \(x\) is a limit point of \(\overline{A}\), then it must have at least one limit point \(y\) in an \(\epsilon\)-neighbourhood.

We consider two cases.

- \(y\) is in \(A\): Then \(\overline{\overline A}\) is a limit point of \(A\) and thus must exist in \(\overline{A}\).

-

\(y\) is a limit point of \(A\): Then, \(y\) itself must also have a point \(z\) in \(A\) in an arbitrary \(\epsilon\)-neightbourhood. Then, the Triangle Inequality gives us: \(d(x,z) \leq d(x,y) + d(y,z)\) We have \(d(x,y)<\epsilon\) and \(d(y,z)<\epsilon\), therefore we get: \(d(x,z)<2\epsilon\)

Thus, we can conclude that \(x\) also has a point in \(A\) in an arbitrary \(2\epsilon\) neighbourhood, and is thus also a limit point of \(A\), and thus has to exist in \(\overline{A}\).

Thus, all limit points of \(\overline{A}\) exist in \(\overline{A}\), and hence we can conclude that \(\overline{\overline A} = \overline{A}\).

\[\blacksquare\]Shuffling two sequences \(<x_1>\) and \(<x_2>\) with limit points \(L_1\) and \(L_2\) respectively, yields a sequence \(x_3\) with two limit points \(L_1\) and \(L_2\).

Consider any two sequences \(<x_1>\in A\) and \(<x_2>\in B\) with limit points \(L_1\) and \(L_2\). Then let \(<x_3>\in A \cup B\) be the result of any shuffling of these two sequences. Then \(<x_3>\) will have limit points \(L_1\) and \(L_2\), and thus the closure of \(A \cup B\) will contain \(L_1\) and \(L_2\), and no new limit points.

If either sequence does not converge to a limit, no new limit points are introduced during the union. Thus, we have proven that combining two sequences does not introduce any new limit points in the resulting sequence. Then it follows that: \(\overline{A \cup B} = \overline{A} \cup \overline{B}\)

\[\blacksquare\]\(\overline{A} \cap \overline{B}\) is a closed set, since \(\overline{A}\) and \(\overline{B}\) are closed sets, and it contains \(A \cap B\). Also, \(\overline{A \cap B}\) is the smallest closed set covering \(A \cap B\). Thus \(\overline{A \cap B} \subset \overline{A} \cap \overline{B}\).

\[\blacksquare\]1.3.10. A point \(x\) not belonging to a closed set \(M \subset (X, d)\) always has a nonzero distance from \(M\). To prove this, show that \(x \in \overline{A}\) if and only if \(D(x, A) = 0\) (cf. Prob. 10, Sec. 1.2); here \(A\) is any nonempty subset of \(X\).

Proof:

We know that \(D(x, A)=\inf d(x,y), y \in M\).

Assume that \(x\in A\). Since d(x,x)=0, we have \(D(x,A)=\inf d(x,y), y \in A = d(x,x) = 0\)

Conversely, assume that \(D(x,A)=0\). Since \(d(x,y)=0\) if \(x=y\), from the definition of \(D(x,A)=\inf d(x,y), y \in A\), the value of \(y\) for which \(d(x,y)=0\) has to be \(x\). That is, \(y=x\). Since \(y \in A\) by definition, we conclude that \(x \in A\).

\[\blacksquare\]Alternative Proof Since \(X\) does not belong to the closed set \(A\), it belongs to the open set \(A'\). Thus, there exists an \(\epsilon>0\) for which the following open ball exists: \(B_\epsilon(x,r)\in A'\).

Any larger ball would intersect with the set \(A\). Since \(\epsilon>0\), there is always a nonzero distance between \(x\) and \(A\).

\[\blacksquare\]1.3.11. (Boundary) A boundary point \(x\) of a set \(A \subset (X, d)\) is a point of \(X\) (which may or may not belong to \(A\)) such that every neighbourhood of \(x\) contains points of \(A\) as well as points not belonging to \(A\); and the boundary (or frontier) of \(A\) is the set of all boundary points of \(A\). Describe the boundary of

(a) the intervals \((-1,1)\), \([-1,1)\), \([-1,1]\) on \(\mathbb{R}\)

(b) the set of all rational numbers on \(\mathbb{R}\)

(c) the disks \({z : \vert z \vert < 1} \subset C\) and \({z : \vert z \vert \leq 1} \subset C\).

Answer:

(a) The boundary of \((-1,1)\), \([-1,1)\), \([-1,1]\) is \(\{-1,1\}\).

(b) Every neighbourhood of a rational definitely contains a real number. The boundary point itself counts as a point in the set in its neighbourhood. Thus, the boundary in this case is \(\mathbb{R}\).

(c) The unit circle centered at the origin is the boundary in both cases.

1.3.12. (Space \(B[a, b]\)) Show that \(B[a, b]\), \(a < b\), is not separable. (Cf. 1.2-2.)

Proof:

Choose the family of functions as below:

\[f_n(x)=\begin{cases} 0 & \text{ if } x=n \\ 1 & \text{ if } x \neq n \end{cases}, n \in \mathbb{R}\]Then the \(d(f_m(x), f_n(x))=\sup \vert f_m(x)-f_n(x)\vert = 1\) unless \(m=n\). Therefore, all distinct functions in this family (examples are \(f_{2.5}(x)\) and \(f_\sqrt{2}(x)\)) are separated by \(1\).

The number of these functions is uncountable, since \(n\) corresponds to the real number line. Each of these functions can be represented by a point in \(B[a, b]\) space, separated by \(1\). An open ball of \(\frac{1}{2}\) around each of them do not intersect each other.

For \(B[a, b]\) to be separable, a countable set, say \(M\), must be dense in \(B[a, b]\). For this, each ball must contain at least one element of \(M\). Since the number of balls is uncountable, \(M\) is also uncountable, and thus \(B[a, b]\) is not separable.

\[\blacksquare\]1.3.13. Show that a metric space \(X\) is separable if and only if \(X\) has a countable subset \(Y\) with the following property. For every \(\epsilon > 0\) and every \(x \in X\) there is a \(y \in Y\) such that \(d(x, y) < \epsilon\).

Proof:

Assume that \(X\) has a countable subset \(Y\) with the following property: for every \(\epsilon > 0\) and every \(x \in X\) there is a \(y \in Y\) such that \(d(x, y) < \epsilon\).

This means, every neighbourhood of \(x \in X\) contains a \(y \in Y\). This \(x\) may not actually exist in \(Y\). Then \(x\) is a limit point of \(M\). Since \(x\) is arbitrary, the entire metric space \(X\) consists of limit points of \(M\), and thus \(X \subset \overline{Y}\) (since \(\overline{Y}\) could conceivably consist of more limit points not in \(X\)).

We know that \(X\), being a metric space, is closed (and open, but that is not of interest here). However, we also know that \(\overline{Y}\) is the smallest closed set covering \(Y\). This implies that \(\overline{Y} \subset X\).

Putting the above set membership relations together, we get:

\[\overline{Y}=X\] \[\blacksquare\]Assume that the metric space \(X\) is separable. Then \(\overline{Y}=X\).

Let \(x \in X\). Then, there are two possibilities.

- \(x\) is a limit point of \(Y\).

- \(x\) is equal to a member of \(Y\).

If \(x\) is a limit point of \(Y\), then every neighbourhood of this \(x\) contains a point \(y \in Y\), and we are done. If \(x\) is equal to a member of \(Y\), then every neighbourhood of this \(x\) contains a point \(y \in Y\) by default, since \(x=y\).

\[\blacksquare\]1.3.14. (Continuous mapping) Show that a mapping \(T: X \rightarrow Y\) is continuous if and only if the inverse image of any closed set \(M \subset Y\) is a closed set in X.

Proof

Assume that the image \(Y\) and its pre-image \(X\) are closed sets. Then \(X'\) and \(Y'\) are open sets.

We know that: \(X'=TX'=Y'\), i.e.: \(T:X' \rightarrow Y'\).

We know that if the inverse image of an open set is open, the function is continuous. Thus, \(T\) is continuous.

\[\blacksquare\]Conversely, assume that the image \(Y\) is closed, and \(T\) is continuous. Then \(Y'\) is an open set.

Since \(T\) is continuous, \(T^{-1}Y'\) is also open. Since \(Y'=TX'\), we have \(X'=T^{-1}Y'\).Hence, \(X'\) is open.

It follows then that \(X\) is closed.

\[\blacksquare\]1.3.15. Show that the image of an open set under a continuous mapping need not be open.

Answer:

\(f(x)=1, x \in (0,1)\) is one such example, since the image of \(f(x)\) is \(\{1\}\), which is closed (its complement \((-\infty,1) \cup (1, +\infty)\) is open), even though the domain \((0,1)\) is open.

tags: Mathematics - Proof - Functional Analysis - Pure Mathematics - Kreyszig